October 17-19, 2020

The spring and summer of 2020 came and went and I still had not been to the Sierra.

Countless others were more intimately touched by the absolute shitstorm of 2020, but in my little world, missing an entire year of mountain activities was a disturbing prospect. Both of my Big Sierra Trips fell through due to smoke, one permanently and the other mercifully transplanted at the last minute to the Ruby Mountains of northeastern Nevada. But not a single minute had been spent in my big bouncy castle in the sky: the goddamn Sierra Nevada.

But in mid-October, an unusually good weather window opened up. Covid, while far from solved, was at least better understood (and experiencing a lull before its raging return later in the fall and winter). A group was assembled and an Emigrant Wilderness route passed around.

But the wind shifted the night before, saturating Emigrant-adjacent sensors with smoke drifting north from the gigantic Creek Fire. Could the Sierra gods truly deny me even this meager weekend?

We scrambled for a plan B and fortunately didn’t have to look far: just to the east, on the other side of Sonora Pass, a sliver of Hoover Wilderness was open. And that wilderness looked good: permits were quota (and dollar) free, the east side was a good deal less smoky, and while the terrain was higher than our planned route, the weather was warm enough that we wouldn’t freeze.

A half hour into our drive, I realized that I’d left my trekking poles at home. This was annoying, but doubly so since one of them was required to hold up my tent! Fortunately, a quick stop at Big 5 in Oakdale netted some aluminum poles, and we were off.

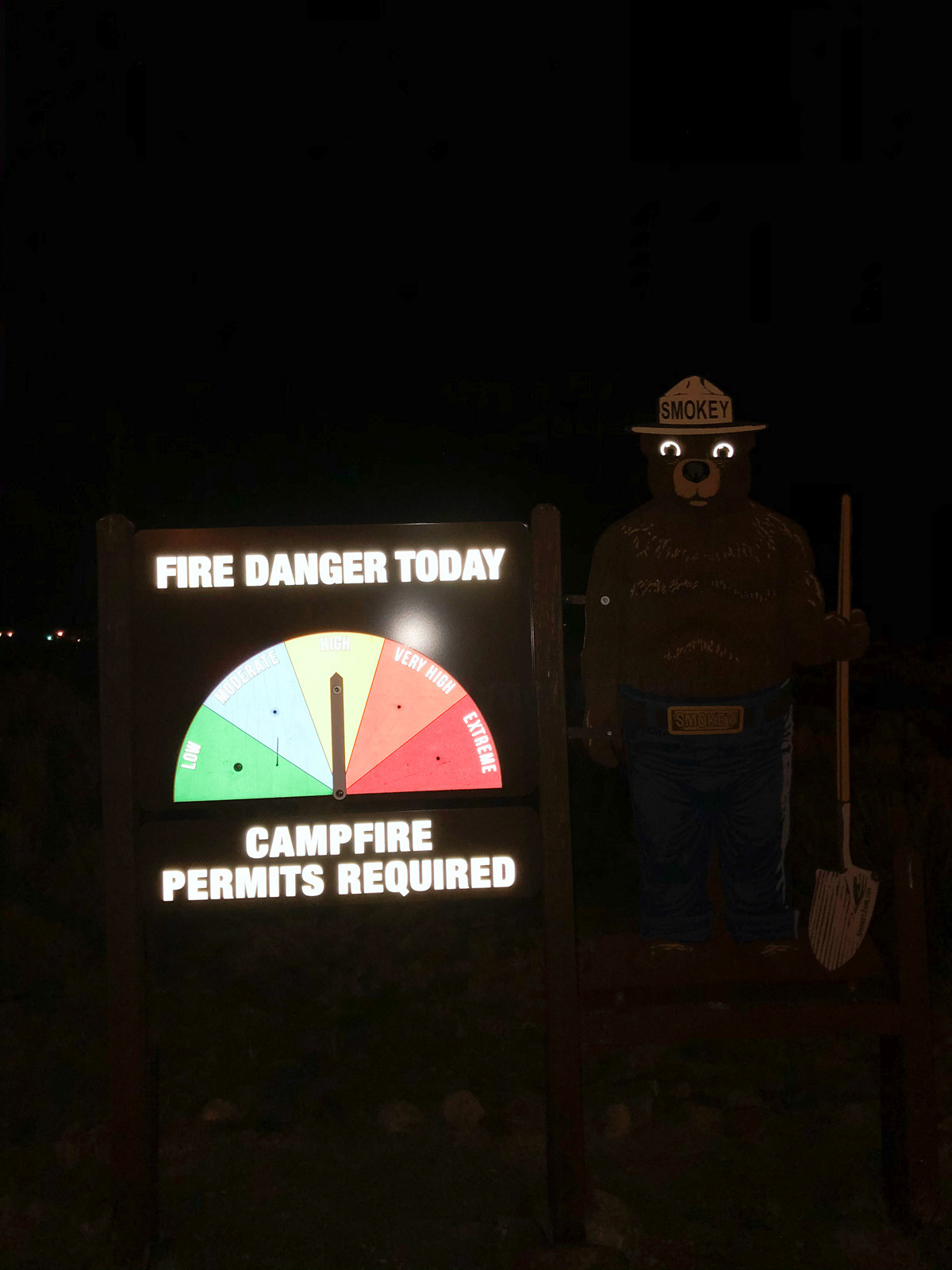

We whizzed over Sonora Pass in the dark and soon enough were parked outside the Bridgeport Ranger Station. We couldn’t help noticing that it was, literally, freezing. Strangely, the forecast where we were going, a full 3000 feet higher, was warmer than Bridgeport. We bundled up and waited for the other car to arrive.

We managed to find a site in the pitch dark at Annet’s Mono Village and hopefully didn’t wake anyone up in the process.

After a short night of sleep we were on our way.

The first couple of miles wound through gorgeous, flat meadows alive with the pleasant (**albeit inherently inferior**) West Coast version of fall color.

At a particular rock -- described by Secor as “table sized” -- we left the proper trail and headed south towards Little Slide Canyon.

A well-trod use trail crossed Robinson Creek (a rock-hopable trickle by mid-October of this low snow year) before flinging us up a steep hillside.

Despite the rough, talus-choked terrain of Little Slide Canyon, the use trail was generally easy to follow. Little Slide is not particularly grand (“Little,” after all) or easy to photograph, but it’s quite beautiful. I was so happy to be back in the Sierra.

The terrain of the canyon changed over time, but the sustained steepness was our companion all morning -- about 2500 feet in 3 miles.

Eventually we reached the striking feature known as the Incredible Hulk, a popular rock climbing spot and the reason for the cruise-y use trail.

The Hulk cantilevers out beautifully from the rest of the canyon wall. (A single, two-person tent was set up, and we heard intermittent whooping and yelping from above, but couldn’t spot any tiny humans against the towering structure.)

A less clear use trail persisted most of the way to Ice Lake, first passing a meager patch of winter still hanging on for dear life.

The trail understandably faded out in the steep, jumbled bushwack required to get around Ice Lake's east side.

The west side of Ice Lake looks like stadium seating for a performance.

Ice Lake was surprisingly nice and we paused for a long time in the dry grass at its bank.

We ascended the final bit to Ice Lake Pass…

...and dropped into Yosemite’s northernmost territory, with just a hint of (Big) Slide Canyon in the distance.

We traversed a lovely meadow and startled two huge bucks, one of whom streaked across us to reach his companion. This was virtually the only wildlife we would see.

Along a dried up seasonal stream bed, we came across a camera. Sincere apologies to the ranger that downloaded its contents to find several stupid photos of us discovering the (impressively well-hidden) device.

We intersected a trail that lead us down towards Slide Canyon through a gorgeous pine forest dappled in honey’d afternoon light. It was not adequately photographed, you’ll just have to take my word for it. It was 3:30 PM, but shadows were long and it looked like sunset was approaching. October!

We soon bottomed out at the canyon, which was massive and gorgeous.

Slide Canyon had been on my list for years and it was so nice to finally be there. (A bit of haze was noticeable from a light north wind blowing down the canyon.)

We quickly came to the Slide itself -- a massive rockslide that once upon a time sheared off the western wall, throwing rocks the size of trucks or even small houses to the far side of the canyon. It was hard (for me at least) to adequately photograph how immense it truly is. A worthy feature to name a canyon after.

Fortunately, there is a great use trail snaking through the trees at the eastern edge of the Slide that avoids virtually the entire thing. Without that, navigating it would be tough sledding.

We walked for another few minutes before finding a lightly used spot to camp in the trees. We lost the sun by 4:30 PM, as the sun dropped behind the towering canyon wall.

The forecast called for freezing-ish temperatures, but it was probably closer to 40. The previous night had been the new moon, so the stars were amazing: the Milky Way was easily visible, along with shooting stars, a few planes, and an endless string of satellites.

We dawdled at camp in the chilly morning, hoping the sun might soon rise over the canyon wall before we had to get going. We eventually gave up and started walking.

The sun eventually made its entrance.

Soon enough, we reached the large unnamed meadow marking our next move...

...climbing over the canyon's western wall at the only real break in its imposing facade.

The climb was a beast -- 1,000 feet of elevation gain in about 3/4ths of a mile.

Looking back.

At the top, we were greeted by a much appreciated expanse of flat alpine tundra at the head of Crazy Mule Gulch.

Looking down at the rest of Crazy Mule Gulch, which looks to be rarely visited.

From here, we did a bit of unphotographed navigating to cross Suicide Ridge, which, at least on the route we took, was fairly easy and not necessarily deserving of such an emo name. After a few ups, downs and arounds, we topped out above Rock Island Lake.

Rock Island sits in another surprisingly flat expanse of alpine tundra.

Some other recent visitors at the beach.

Despite a stiff breeze, two deranged hikers took a dip.

After a long break, we headed over the low point at the northern end of the basin.

Possibly the best part of hiking: seeing what’s on the other side.

We got a bit lucky staying high and traversing north around the bowl towards Rock Island Pass. There looked to be many opportunities to become moderately cliffed out, but we made it straight to the pass and its sign noting our exit from Yosemite and return to Hoover Wilderness.

Just beyond the border was Snow Lake, the topmost lake feeding Robinson Creek, which spills thousands of feet down to Mono Village. We had crossed the creek down below, at the very beginning of the trip.

The return of switchbacks.

Soon enough we made it to Crown Lake.

We set up in a huge, flat expanse that was supremely sheltered from the not-insignificant north wind. It was a perfect spot, though likely holds a seasonal stream earlier in the season.

In regular life, Nate spends three minutes a day in a near-freezing “cold tub,” so squatting motionless in a Sierra lake for several minutes was nothing to him. It’s “all about the breath,” he says. OK, Nate!

Crown Lake, a good lake.

After another long, unseasonably warm (i.e. cold, but not freezing) October night, we were off again. We chose a fun and entirely unnecessary sidehill-y route back to the trail.

And from there it was pretty much smooth sailing through glorious forest and switchbacking trail.

We passed Robinson Lakes, looking quite low.

Fall colors returned at lower elevations.

Eventually Barney Lake appeared on the horizon.

It is a lovely spot! And only 4 miles from the trailhead.

It was a quick descent through more yellowing aspen.

We found ourselves in the glorious pine forest at the edge of Mono Village.

And soon enough, we were back to electricity, soda, and Trump signs outside of RVs (you really brought your Fascist lawn sign to the campground, bro?).

From there it was back to Bridgeport, Sonora Pass, 75 miles per hour and the rest of our lives.

For the nerds:

Mono Village > Robinson Creek trail > Little Slide Canyon > (Big) Slide Canyon >

the fairly obvious/only gully up the western wall of Slide Canyon > northern bit of Crazy Mule Gulch >

Suicide Ridge > Rock Island Lake > Rock Island Pass > trail back to Mono Village