August 19-23, 2021

Each summer, a new set of names arrive to claw summer away from us. Carr, Creek, Nuns, River, Walker, Rough, August, Kincade. These unplanned poetries enter the lexicon and wreak havoc on land and life while spewing sooty and invisible particulate for hundreds or thousands of miles in whichever direction the wind blows.

In 2021, the Dixie, Tamarack and Caldor combined to make the late summer another indelibly smoky one for California and the Sierra Nevada. Traditionally, August and September are the finest months in the high country: fewer people, fewer bugs, less rain, lower stream crossings. But that window looks to be shifting into July and even June as extended drought, poor forest management and climate change render much of the West precariously fire prone by mid-summer.

Indeed, this trip was already a do-over from 2020, another brutal fire season (Creek, August Complex, SCU Lightning Complex).

The plan was an out and back to the McGee Lakes Basin via Lamarck Col.

For a few weeks, a steady west wind had kept much of the smoke from California’s various and growing fires flowing into the state of Nevada. But a day or two before our trip, a shift in wind sent smoke streaming into the High Sierra.

The viability of the trip -- entirely unknowable but cruelly easy to theorize about -- occupied much of the drive.

The western side of Yosemite was very hazy and smelled strongly of smoke…

…while the east side of Tioga Pass was much clearer. This kind of local variability in smoke is one of the frustrating aspects of fire season in the mountains.

At the North Lake trailhead, a woman returning from Humphreys Basin said it had been crystal clear and bright until this morning. Another one of our perfectly timed trips!

The evening light was soft and wonderful on the short climb, and quite clear here on the east side of the Sierra crest.

Surprisingly, there are not a ton of good campsites at Lower Lamarck Lake. We slotted ourselves into a mediocre and possibly illegal spot to eat our Schaat’s sandwiches.

Night comes earlier by late August and my new-ish phone could finally show off the surreal, painterly things it does with very little light.

We were off by 8 AM the next morning.

A dog caught up with us and, a few minutes later, its owner came charging up in a daypack.

He had been born and raised in Bishop, where he now worked on “mammal stuff” in the Sierra: mostly mountain lions and bighorn sheep. He said that there are hundreds of mountain lions in the Sierra. (“Anywhere there are deer, there are lions.”) This was surprising news to me given how few sightings there are; via the internet, I'm aware of only a couple.

I was ready to assault him with questions all morning, but I eventually let him pass by on his uphill run to Lamarck Col and back – a level of fitness and altitude acclimation that is hard to fathom.

The terrain turned full moonscape. The trail was a sandy slog, but easy to follow until quite near the top, where some benign Choose Your Own Adventure took over.

Lamarck Col.

This slope is typically covered in snow, with braided boot paths laid in by previous hikers. But in this epically low snow year, it looked like the best route would be straight up the smaller boulders to the left of the remaining ice field. (The Muir Hut-shaped rock just left of center on the ridge is our destination.)

It turned out there was a good switchbacking trail nearly the whole way up. Given that this slope is covered in snow for much of the year (albeit less so in the last decade or two), I wonder when this use trail came into existence.

The iconic sign at the top – nearly 13,000 feet on our first full day!

The view down Darwin Canyon on the other side.

We started down the most obvious use trail and lost it pretty quickly. The entire descent seemed to consist of a million intersecting use trails leading to nowhere. Upon consultation, GPS told us we were in the right spot, but we did not hit upon a useful trail.

The striking, barren lake at the head of the canyon.

As the terrain leveled out a bit, we ran into a lovely older couple and soon after hit on a good trail that lead us down to our first lake.

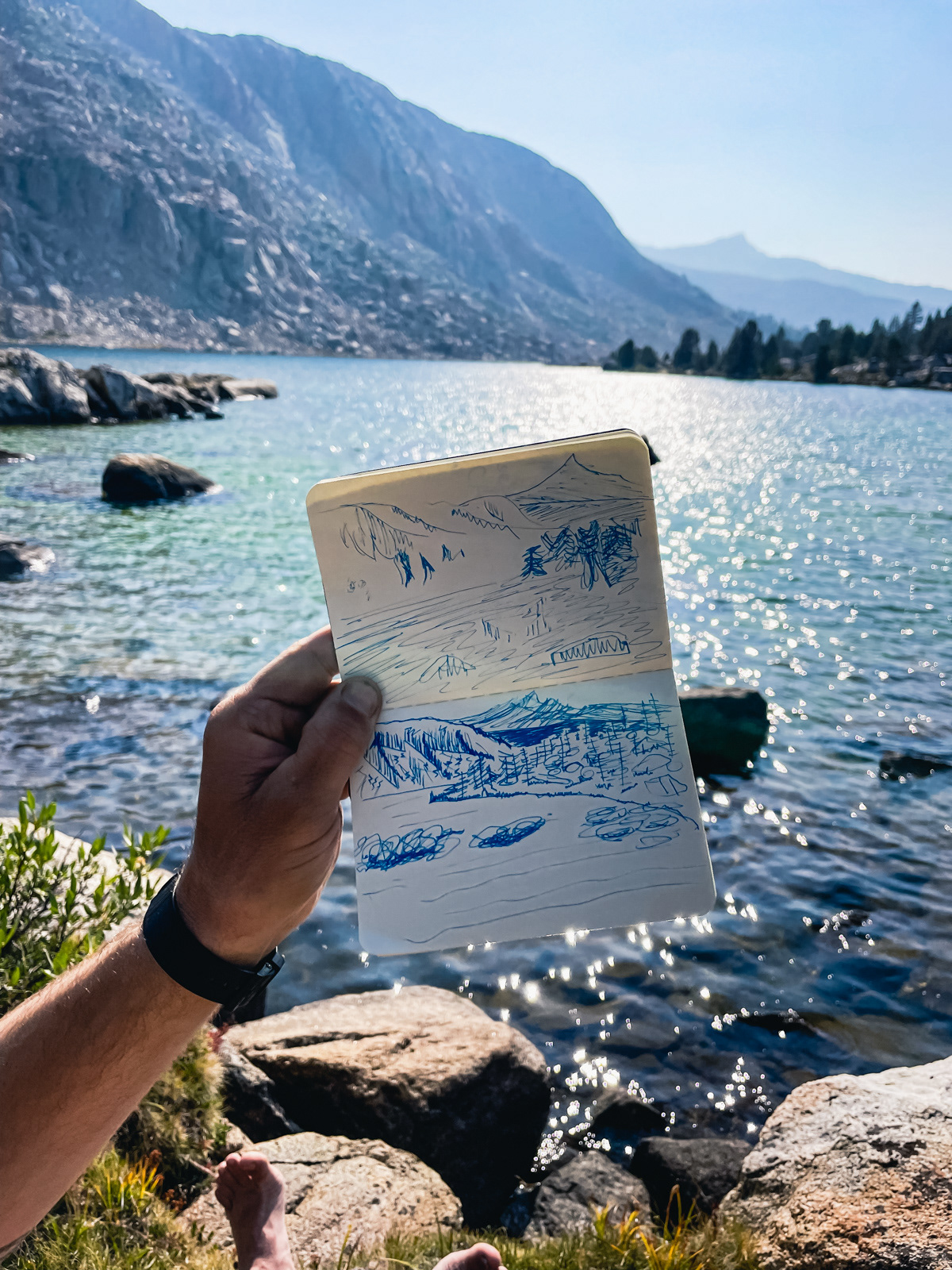

It is a glorious lake: a vibrant and indescribable color with a small beach and grass (a rarity in this rockbound area). We took a long break.

The traverse around the string of four Darwin Lakes is mostly easy, with two sections of massive boulders. The rock is stable and ancient — the issue was carving a reasonable path through the antiquity, which took some time and thought.

We kept descending, finding and losing the vague trail.

Darwin Bench.

Evolution Valley (sort of) revealed itself. The haze was much thicker now.

We hit the JMT and passed a memorable spot where the three of us had had breakfast together five years prior. The mountain the background is called The Hermit, and our plan was to circumnavigate it.

We soon reached Evolution Lake.

It is a profoundly situated lake, and very popular. It’s also huge and surrounded by forgiving terrain where we easily found a spot away from the modest crowd of tents along its shore.

We were very, very tired. Lamarck Col deserves its reputation as a quick but especially draining route into the high country.

We started to consider a change of plan. While we felt OK with the degree of smoke health-wise, McGee Lakes sounded special, epic, grand; exactly the kind of far-off vistas that would be washed out in current conditions.

Some of the best advice I have for our new smoky hiking reality is to stay near or below treeline, in the realm of near term beauty. The face melting vistas are simply less melty under smoke, whereas the world up close is as beautiful as ever.

We decided to sleep on it.

In the morning, we hemmed and hawed and eventually agreed to reroute ourselves north through Evolution Valley, Piute Canyon, and Piute Pass. It would be a much different trip: lower, busier, and almost totally trailbound. (And with Lamarck Col so fresh in our memories, the idea of schlepping back over it in two days sounded cruel.) I'm still not sure if we made the right choice.

We descended quickly to Evolution Valley.

Evolution Creek was running slow and very low.

We descended to Goddard Canyon.

After a few mindless miles, the canyon opened up into a stunning landscape of huge waterfalls and insanely carved rocks.

We had walked these trails together five years prior – my second ever visit to the High Sierra – and it was nice to repeat this landscape in the other direction years later. It’s an exhilarating stretch of the JMT, where the power of water and glacier are on full display.

I hadn’t eaten enough and was close to bonking as we arrived at the Piute Bridge. We had considered pushing up the canyon but after a swim and snack, we decided that this was a good spot.

The area is crawling with campsites, but it’s gigantic and we barely noticed the 3 or 4 other groups hundreds of feet away. (I wonder if the existence of MTR a few miles down the trail keeps attendance down?)

We settled in for a long sleep.

We were again walking by 8. Piute Canyon is a gem. In the cool morning light, the towering cliff faces looked amazing (but refused to be photographed well).

2/3rds of us took a dip at some glorious slabs halfway up the canyon.

We kept climbing and took a long lunch break in Hutchinson Meadow.

Previous visitor.

We turned right and headed up toward Humphrey’s Basin.

Soon enough we ventured off trail towards the Golden Trout Lakes, where we restored ourselves in the water. The lake is mucky and shallow. Each step set off atomic bombs of muck – gross but worth it. I imagine that these lakes are on their way to becoming meadows.

Later we took a Sunset Club trip up the striking rock formation separating Upper and Lower Golden Trout Lakes.

There were exceptional views in all directions.

Looking north over the basin to Mount Humphrey.

The moody, smoky sunset did not disappoint.

It had smelled more of smoke overnight than at any other point of the trip.

As we got going, Humphrey’s Basin was cloaked in sullen haze.

A dour final view of the interior Sierra, looking west from near Paiute Pass.

The descent passed quickly.

And just like that we were back in the modern world.

On one hand – what a gift it is to be in this profound range.

On the other hand -- it takes a lot of time and energy to get up into the alpine just to walk through smoky landscapes while inhaling unhealthy levels of particulate.

To avoid smoke, the typical recommendation is to stay high, but on this trip we often found the opposite: our clearest night was at 8,000 feet, our worst near 11,000. The convoluted nature of mountainous terrain makes smoke forecasting a complex problem.

What appears less ambiguous is that, in many years, August and beyond in the Sierra will likely harbor at least some smoke. While this was a fantastic trip through stunning country, I'm not sure how viable or enjoyable year after year of smoke-filled trips would be. To my eyes, haze strips away a surprising amount of the ludicrous beauty and overwhelming scale of the range. And even if one is amenable to smoky trips, the emerging science of long term PM2.5 inhalation is not encouraging.

This is our reality for the foreseeable future. The solutions to climate change and forest management are within our grasp scientifically, yet are politically and culturally intractable in this country and would take decades to show meaningful results anyway. All we can do is hope for more snow, less heat (and wind), and cooler heads to prevail. See you in July!