August 15 - 19, 2024

Five years ago I drew up a trip, saved it in my notes as “Lonely Copper Cloud,” and forgot all about it.

Lonely Copper Cloud: a bit of refrigerator magnet poetry culled from a lake (Lonely), an unusual off trail pass (Copper Mine), and a semi-famous canyon (Cloud). These southern Sierra treasures would be linked together by an inelegant curlicue of a route that takes in the entirety of two classic canyons along with a few profound lakes. Life (and other Sierra trips) got in the way of this particular outing for half a decade, but finally it was resuscitated, maps were printed, alarms rang at 4:30 AM, and we were hiking out of Wolverton by 11:30.

At Panther Gap, we got our first big view – one that unfortunately included the Coffee Pot Fire, which had been burning for a couple weeks west of Mineral King. The fire was mostly churning along low and slow, but our forecast looked windy and this afternoon’s plume was already nastier than I had expected.

We turned east and followed the beautiful high trail towards Alta Meadow, where we took a long break, tired from the elevation and our early alarms.

We eventually got going again, now following an old unmaintained trail. Luckily, we managed to mostly stick to its faint outline. One final, brutal climb brought us to a striking view of Buck Canyon and beyond.

It was after 5 PM, and while catching our breath on this beautiful ridge, one of our group accidentally gulped down a 100mg caffeine gel. This meant that he would barely sleep later on, but in the moment he sprinted through our last climb of the day and was at Moose Lake almost instantly.

Moose Lake is huge and cool.

We scouted around the south side and found that the shoreline is not exactly overrun with flat, campable spots, especially for a group of four. We eventually sorted ourselves out on the hillside facing south toward Mineral King, and took in the evening light as it changed the complexion of these brilliant mountains.

Mmm hmm.

!!!

Moose night.

We had a short day planned, and took our time in the morning. Half the group went for a dip at the bracing hour of 9 AM, which is simply not a part of my lifestyle.

We left the lake and wandered north to a view above Table Meadows that looked intriguing on the map, but a bit less so in reality.

We dragged ourselves east and south across some messy Tablelands stuff. Smoke was starting to coil its way into the Kaweah drainage. We ran into a large group at the top of Pterodactyl Pass that had camped on the north side of Moose Lake the previous night.

We were at Lonely Lake by 3 PM, camping in the exact spot I had five years prior.

We dropped to the lake, swam, snacked and arranged ourselves along its narrow beach for a long time.

I love this lake!

The horn above Lonely Lake is one of my favorite features in the Sierra.

While down at the lake, a marmot had an early dinner of my friends’ trekking poles.

After our own dinner, we walked up to the escarpment to the north, something I had also done five years ago.

We were greeted by this view of Big Bird Lake, where we would be in two days’ time.

Lonely night.

It was windy overnight, something that was not appreciated by the cowboy campers amongst us. We were walking by 8:30 AM, and on top of Horn Col by 9. The pass looks like an unclimbable vertical wall from afar, but is no problem when approached from its north side.

The Horn! (Which looks terribly foreshortened here – it’s huge.)

Looking east across the top of Deadman Canyon from Horn Col. We were heading to Copper Mine Pass, which is the small dip on the left side where a wisp of cloud is peaking out above a small U-shaped snowfield.

The view down Deadman Canyon and across many layers of Sierra ridges, all the way to (I think?) the Palisade Crest.

We made our way across the head of the canyon, up and down smooth fins of granite. We crossed many burbling, snowmelt streams that were just beginning their journey down to become part of the South Fork Kings.

Soon enough we were at the namesake copper mine – a quixotic operation funded by legendary Sierra explorer William B. Wallace.

Here in the ether below 12,000 feet and many hard miles from the nearest road seems like a hell of a place to stake your copper claim. It is to the High Sierra’s enormous luck and benefit that it contains little in the way of easily exploitable material. Even Mineral King, named with such promise and enthusiasm, was a bust. Most notably for the high country, the gold that built California’s first fortunes was found miles to the west, in the low foothills of the range.

All of this meant that in August of 2024, we were able to find ourselves alone in a vast, roadless expanse of alpine wilderness inside of the most populous state in the country.

Remnants.

We climbed the last steep bits of crumbly shale to the pass. At the top, we were greeted by a voracious wind that practically knocked us over.

The south side of Copper Mine Pass looks very steep on the map, and I wondered how it would present here in real life.

Turns out, it is definitely steep, and would be a rocky, crumbly, side-hilling mess without the nicely constructed use trail winding along the south side of the ridge between Deadman and Cloud Canyon. Wallace had staked a similar mineral claim in Cloud Canyon in the 1880’s, and this extant trail is likely the work of his miners, who at some point required consistent access between the heads of the two canyons – just as we did today.

Lion Lake, looking stunning, austere, and remote.

The wind was unrelenting, and we walked the ridge small and hunched over, braced against the gusts. Naturally, this wind was a boon for fire, and smoke from Coffee Pot was rushing along the ridge with us.

Eventually we reached the obvious drop into Cloud Canyon.

The top few hundred feet off the pass are steep and loose: rock slide central. There are intersecting use trails that lend some form to the otherwise chaotic world of angular rock, but one of us still managed to cut his hand open while sliding his way down this mess.

Soon the grade mellowed out, leaving us in a land of small boulders.

Cloud Canyon was also named by Wallace, along with his mine: “I named it ‘The Cloud Mine’ because the clouds hung so low overhead.” No such luck today: not a cloud in the sky, unless you counted the smoke.

We kept going north.

Eventually we reached a steep talus slope that took forever to descend and wore our legs all the way out. (This was just east of the 11,000 foot marking between “Ridge” and “Cloud” on the USGS topo.)

We paused, exhausted, in the meager shade of the first tree we’d seen all day. The descent off Copper Mine is long and tough! We eventually descended to the inviting basin below, following a creek painted slowly white by minerals.

We’d finally made it to the brief, flat respite of Upper Cloud Canyon – soft tundra with a rolling creek and towering rock walls.

We took a break just as two Sierra old timers showed up heading the opposite direction. They were delightful. One of them had been out for 14 days already, and both had serious stories to tell.

That said, their beta that the rest of Cloud would be a cruise and that the lower part of Deadman Canyon was choked with impenetrable blowdowns proved to be the exact opposite of our experience (?!).

Indeed – the head-height bushwacking and endless boulder morass between 9500 and 9100 feet was a special kind of Sierra hell for me. Maybe I took the worst possible line in the history of Cloud Canyon? But it was a total sufferfest. This section alone will probably keep me away from Cloud for as long as it takes to forget.

Of course, even this hell came to an end, and we hit the trail. We wanted to check out the semi-famous “Grand Palace Hotel” packers camp, but for some reason could not find any sign of it.

Instead, we cruised down to Big Wet Meadow, where we mercifully stopped for the night. It had been a long, hard day. Cloud Canyon took it out of me. Miraculously, the smoke that had been building all afternoon was nowhere to be found now.

Cloud is to the right of the Whaleback here: we could see much of our afternoon’s walk from this spot.

It was strangely the coldest night of the trip, down here below 9000 feet. We were up and walking by 8 AM. This was to be a long trail day and we hurried down to Roaring River where we took a break and availed ourselves of the pit toilet. My left calf felt a little tweaky, a sensation that thankfully disappeared.

We turned south and headed up Deadman Canyon.

Yesterday’s old timers had warned that lower Deadman was covered in wave after wave of time consuming avalanche debris, but we only came across a few examples, all of which were easily surmounted.

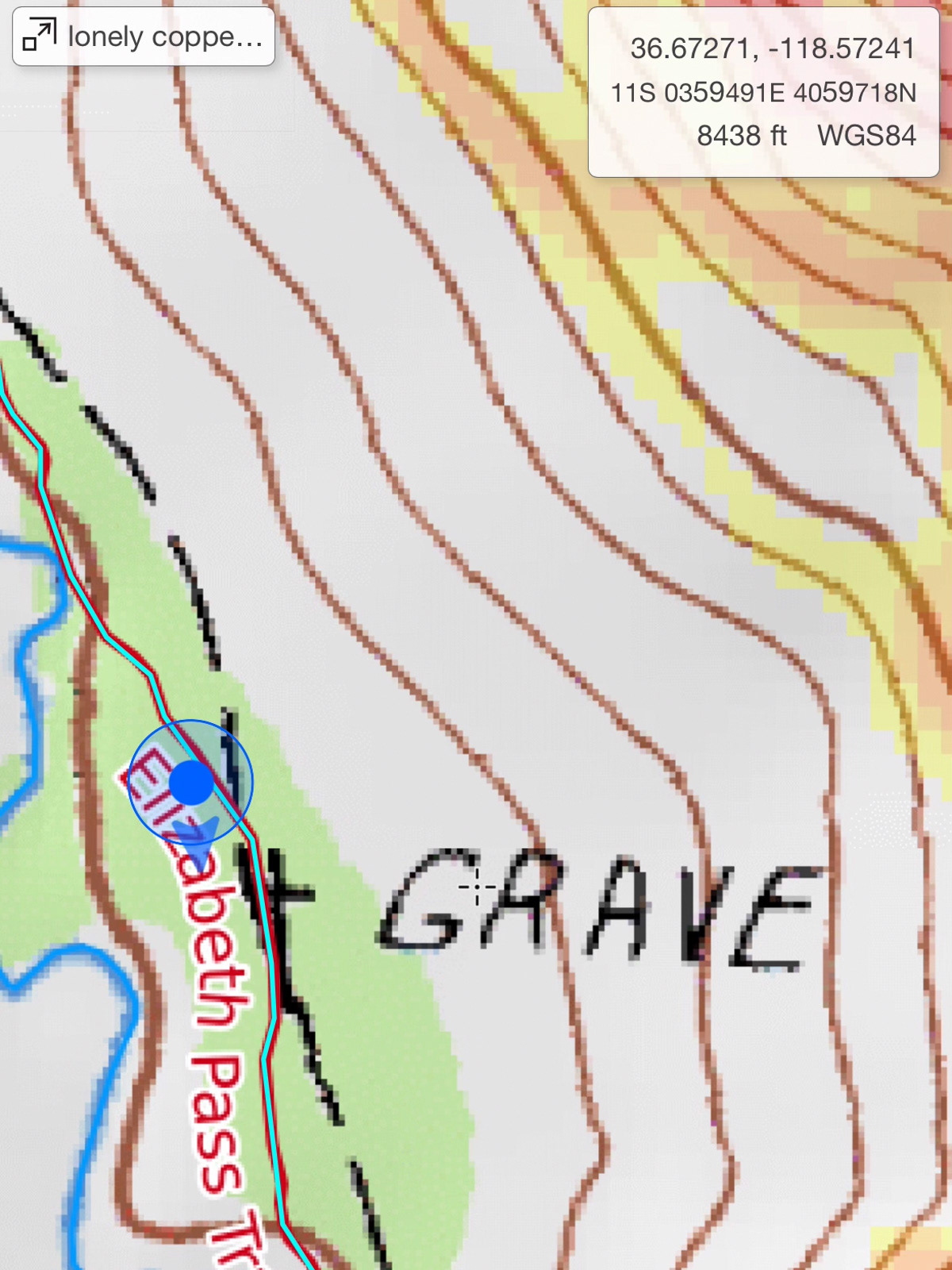

The grave of the old sheepherder who gives the canyon its macabre name.

We kept a steady, easy pace and soon enough were walking the huge expanse of Ranger Meadow.

This was our cue to leave the trail and ascend some steep and glorious slabs toward Big Bird Lake. This is a very cool ascent, and the view back down Deadman is exceptional. We stayed on the northern side of the creek, which is probably the way to go, especially as one gets higher.

Big Bird Lake! Another special Sierra lake.

We all took a dip, set up shop and settled in for our last night.

While picking up our permit, the ranger had mentioned a different route from Big Bird to the lakes above than we had planned to take. He enthusiastically called it a “practically ADA-accessible ramp.” It’s hard to resist that kind of salesmanship!

Looking at it from below, it was easy to scout the ramp. As is often the case, there was one choke point that was harder to judge – was it a simple chute? Or a one foot ledge teetering above a sheer wall of doom? We were about to find out.

Turns out – the ranger wasn’t lying. Welcome to an (almost) ADA chute!

Looking back.

The terrain flattened out briefly as we continued south.

Soon enough we were looking down on the first lake.

From here, it’s a relatively simple climb up and traverse across endless slabs.

Serious polish.

This “High Bird” basin is exceptional, if a little stark.

We reached Tablelands Pass, which is not very pass-like, and the unusual Lake 11,200.

We stopped briefly, before barrelling down through the Tablelands at high speed. I’d done this section before. In fact, this was my third time through the Tablelands in the past five years, and I think I’m ready to take a break. Its unusually open, tabletop topography is appealing, but is perhaps missing some of the romance (?) of my beloved, basin-based Sierra.

We took a break before crossing the final, little mound to Pear Lake and rejoining day hikers and named trails. We’d walked 6 off trail miles in under 3 hours, and we were Tired.

We stopped again at Pear. It had been a clear morning, but smoke suddenly came pouring in. It changed the entire world’s hue within a few minutes, like someone was playing with the color temperature slider on life itself. Surreal.

This just hastened our final, brain-numbed miles down the Lakes Trail to the car, and clean clothes, lunch, highways, parking lots, reality.

Lonely Copper Cloud. A good name, and a good route: moderate cross country interspersed with long trail miles; two perfectly glaciated canyons and a few profound lakes; mostly up in the alpine, but with some particularly engaging pine forest walking as well. These are the kinds of dualities that you want on a Sierra trip, yet I came away from this particular one a little underwhelmed.

My best guess is that it was slightly too alpine for me: from the end of Day 1 (Moose Lake) until the end of Day 3 (Big Wet Meadow), we were above treeline. This wasn’t a surprise – indeed, I had planned it that way. Yet I was surprised by how monotonous it felt to me to be in Rocks-only world for two days straight (and with a big dose of the same on the final morning through the Tablelands). Many Sierra addicts yearn for these austere alpine environments, but two full days of it was not ideal for me. A man yearns for a tree!

But beyond this minor quibble, this was another great trip, and I’d recommend this route to anyone excited about the prospect of a highly alpine, West side trip. The Lonely/Horn/Big Bird area is home to some especially beautiful, swooping granite shapes that seem unique to that area. This southwestern corner of the High Sierra is as cool as they come.